Understanding the New UK R&D Tax Relief Rules for Contracted-Out Activities

New UK R&D tax relief rules for contracted-out activities, effective April 2024, clarify eligibility. Learn HMRC’s criteria and practical examples in this article.

The UK’s R&D tax relief rules for “contracted-out” activities have been updated, effective for accounting periods starting on or after 1 April 2024. These changes clarify which party -either the principal commissioning the R&D or the contractor carrying it out - can claim tax relief for work contributing to research and development outcomes.

Historically, ambiguity surrounded whether the party performing the R&D or the one funding it was eligible for relief. With the introduction of the new rules, HMRC has provided more comprehensive guidance to clarify this aspect of R&D tax claims.

The reforms go beyond mere administration, aligning eligibility with the economic reality of the R&D project. Claims now depend on who initiated the work, defined its objectives, assumed the financial risk, and will reap the benefits.

This article explores the meaning of “contracted out” R&D under the new rules, outlines HMRC’s assessment framework, and shares practical examples based on the most recent draft guidance.

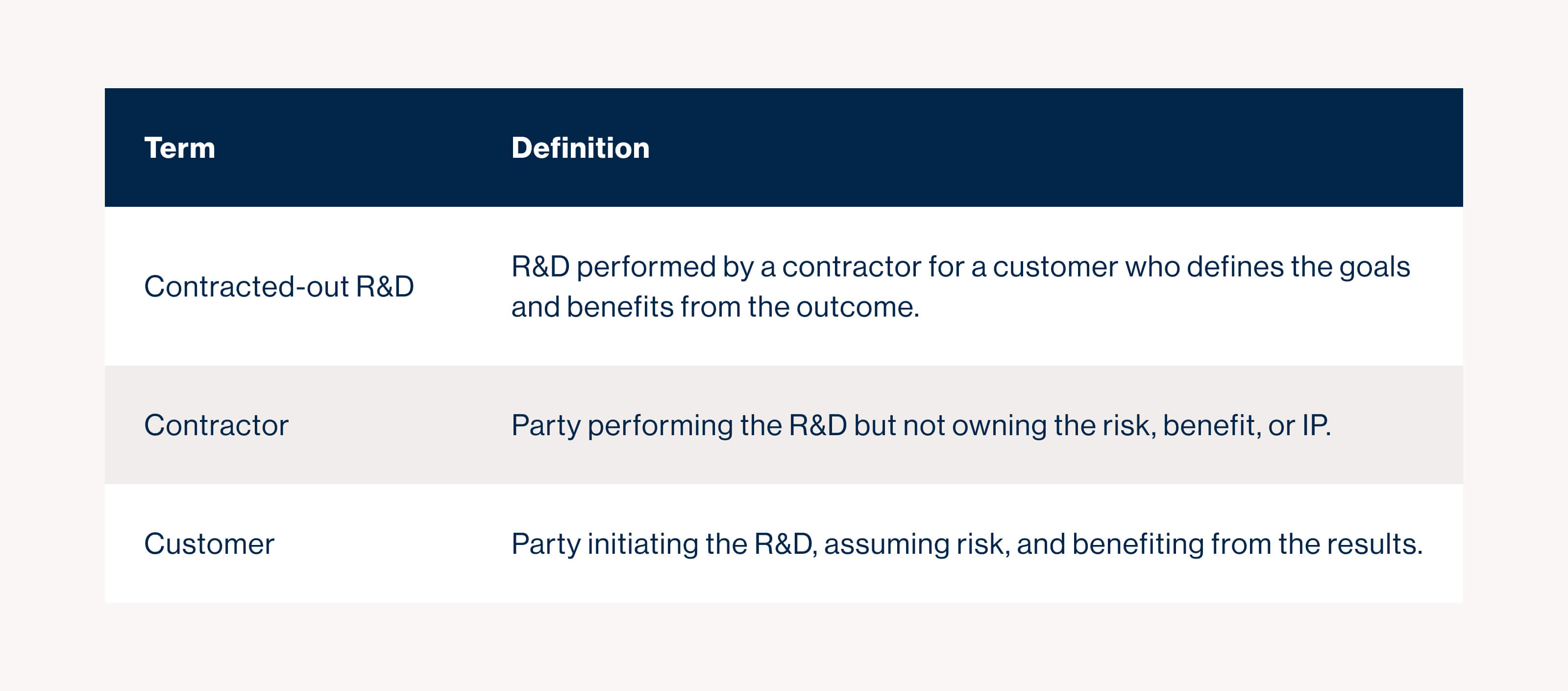

Defining Contracted-Out R&D

In the simplest terms, contracted-out R&D refers to a scenario in which a company—let’s call it the "customer"—pays another party—a "contractor"—to performR&D activities. The distinction that HMRC draws, however, is far more nuanced.The new rules define contracted-out R&D as work that a contractor undertakes not for its own purposes, but to fulfil the objectives of the customer, under terms dictated by the customer, and typically with financial risk and benefit retained by the customer.

What sets contracted-out R&D apart from other forms of outsourcing is the presence of qualifying R&D.That is, the activities must be aimed at overcoming scientific or technological uncertainty. Simply hiring a third party for routine development or technical tasks would not meet this threshold. Likewise, the party performing the R&D cannot claim relief if it was merely executing tasks for a fee, without initiating the innovation or taking on risk.

Section 7.2 of the HMRC draft guidance provides additional insight into the purpose and intention behind the concept of contracted-out R&D:

- Purpose:R&D is considered contracted out when it is undertaken by one party to meet the requirements or business needs of another, as part of the latter's broader business goals. The contractor performs the work, but the benefit is for the customer.

- The Contract: A formal contract, whether written or verbal, is essential in determining the obligations and purpose of the R&D. It need not be labelled as an "R&D contract," but must establish the scope and responsibilities of each party.

- Meeting an Obligation: If the R&D is carried out to meet a specific contractual obligation, particularly one in which the contractor is required to deliver results as per customer specifications, the work is likely to be considered contracted out.

- Intended or Contemplated Purpose: The assessment is based not only on what was explicitly agreed but also on what was intended or contemplated at the outset. HMRC will look at whether R&D was a necessary component of the contract from the beginning, or whether it became necessary only as the project evolved – more on this later.

This emphasis on intention means that businesses must consider how their contracts and negotiations are structured from the outset. Even if R&D is not specifically mentioned, the way obligations are framed and the expectations around innovation can make the difference in determining who holds the right to claim relief.

Intended or Contemplated -HMRC's Four-Factor Assessment

To determine which party can rightfully claim R&D tax relief, HMRC has introduced a multi-factor test.These four dimensions—initiation, specification, financial risk, and benefit—offer a framework through which the commercial substance of each arrangement is assessed. Let’s explore each in more detail.

Initiation

Initiation refers to which party conceived of the R&D project. This is the party that recognised a scientific or technological challenge and decided to address it. If a company identifies a need for innovation within its products, processes, or services, and then commissions R&D activity to address that need, it is considered to have initiated the project. By contrast, if a business is approached by another company and asked to solve a problem defined by the latter, it is acting as a contractor.

Key indicators of initiation include internal R&D strategy documents, risk assessments, feasibility studies, and records showing proactive steps taken before engagement with a third party. A customer that documents a clear innovation gap and seeks a partner to execute part of the R&D is typically the initiator.

Specification

Specification concerns who defined the technical and functional requirements of the project. If the customer provided a detailed brief with set objectives, deliverables, and timelines, this points strongly to them specifying the work. Even where technical freedom is given, overarching constraints or desired outcomes can reflect specification.

Evidence might include written project briefs, scopes of work, contractual milestones, acceptance criteria, or correspondence outlining technical expectations. If a contractor sets its own goals, performs self-directed experimentation, or proposes novel methods unrequested by the customer, this leans toward self-specification and possible eligibility for relief.

Financial Risk

This factor assesses who shoulders the burden if the project fails. A company that pays the contractor regardless of outcome, or covers cost overruns and contingencies, is likely assuming the risk. This is often documented in contracts as fixed-fee arrangements, indemnity clauses, or guaranteed payments.

In contrast, if a contractor only gets paid if certain milestones are reached, or if it must absorb losses from unforeseen issues, this signals financial exposure. Real-world documents tosupport a claim could include contracts with variable pricing, payment holdbacks tied to success, or insurance clauses allocating risk.

Benefit

The final test considers who will benefit from the R&D outputs. This includes ownership of IP, right to exploit results, and exclusivity. If a customer is assigned all IP and commercial advantage, they benefit from the project.

Supporting evidence includes IP assignment clauses, licenses, patents, commercialisation plans, and even internal memos about intended use of the R&D. Contractors who retain rights to incorporate innovations into their own offerings may be seen as beneficiaries and possibly eligible.

Legal and Practical Implications

The introduction of this detailed framework means that businesses must take a proactive and strategic approach to contracting. All too often, contracts are drafted without consideration forR&D tax relief consequences. Companies should now ensure that contracts explicitly outline roles and responsibilities concerning initiation, specification, risk, and benefit.

Moreover, documentation becomes vital. Internal records such as meeting minutes, strategic planning documents, and technical briefs can support a claim by illustrating who initiated and directed the R&D. Payment schedules and IP clauses in contracts must align with the desired treatment. A mismatch between commercial terms and a claim could trigger an HMRC enquiry.

Companies should also regularly review agreements to identify areas of ambiguity or unintended risk allocation.For example, a company might inadvertently pass specification control to a contractor by accepting their proposed scope without amendment. Where R&D incentives form a material part of a business case, legal, tax, and technical teams should collaborate closely from the outset.

Finally, from a contractor’s perspective, being technically competent or conducting advanced work is not enough. Eligibility is rooted in economic substance, not scientific complexity alone. Contractors must ensure their own documentation reflects autonomy, risk, and benefit if they intend to claim.

Examples

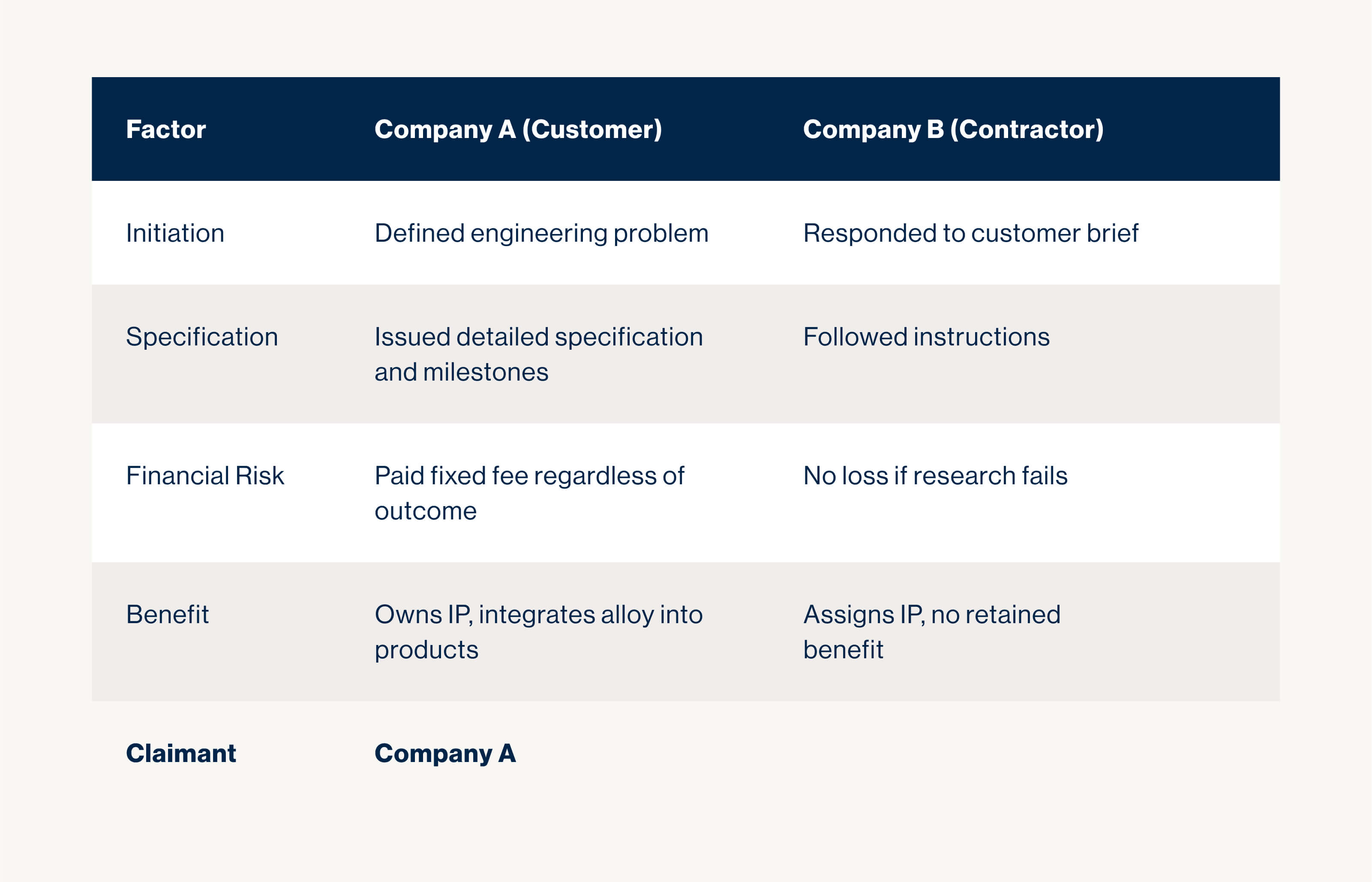

Example 1: Materials Development for Alloys

A UK-based alloys manufacturer(Company A) commissions an advanced materials consultancy (Company B) to create a new heat-resistant alloy for a new manufacturing process it is developing.Company A drafts a 50-page specification document, outlines milestones, and pays £750,000 over 12 months regardless of the research outcome. Company B is contractually obliged to assign all IP to Company A.

Here, Company A initiated the work to solve a known engineering bottleneck, dictated specifications, bears financial risk through unconditional payments, and will benefit commercially through alloy sales. Even though Company B performs highly complex R&D, it is Company A that claims the tax relief.

Example 2: Diagnostic Tool Innovation

Company C, a health tech SME, engages Company D, a machine learning firm, to create an algorithm for early detection of cancerous conditions. Company D designs the algorithm, proposes novel data science techniques, and sets its own objectives and validation procedures. The contract includes a clause allowing Company D to repurpose the technology for other healthcare applications. Payments are milestone-based and contingent on success.

This case is more nuanced. WhileCompany C funded the work, Company D initiated the specific R&D approach ,bore risk through conditional payments, and will benefit by retaining application rights. Therefore, HMRC may deem Company D the rightful claimant.

Example 3: Software Development with Subcontracting

Company E contracts Company F to develop a bespoke ERP system involving a new software architecture. Company F subcontracts part of the work to Company G, a data encryption specialist.Company E issues the technical brief, pays based on time and materials, and owns the final IP. Company F and G both perform qualifying R&D.

Company E initiated, specified, bears financial risk and will benefit. Company F and G act as delivery partners under direction. The R&D tax relief claim sits with Company E. However, if Company G uses the same encryption methods in its own SaaS products and bears some cost of development, it may be able to claim for that portion of work, assuming clear contractual delineation.

Example 4: Overseas ClinicalTrials

Company H, a UK pharma firm, sponsors clinical trials for an infectious disease vaccine in a region where that disease is endemic. Local regulations and population availability make replication in the UK infeasible. Company H coordinates the project and retains all results.

Despite the trials being conducted overseas, the work is eligible under the "wholly unreasonable"exemption due to natural and regulatory conditions. Company H can claim for this overseas expenditure as part of its broader R&D claim.

Impact of Recent Tribunal Decisions

Recent First-tier Tribunal cases, such as those involving Collins Construction Ltd and Stage One CreativeServices Ltd, have influenced HMRC to update its guidance. The tribunals concluded that the companies' expenditures were neither subsidised by their clients nor constituted contracted-out R&D, leading HMRC to revise its stance on these matters.

JudicialCommentary: Key Case Law Developments

CollinsConstruction Ltd v HMRC (2024)

In this landmark case, theFirst-tier Tribunal found in favour of CollinsConstruction Ltd, challenging HMRC’s rigid interpretation of “subsidised expenditure.” HMRC had denied the company’s R&D tax relief claim on the grounds that the R&D was carried out under a customer contract and was therefore subsidised.

Key Findings:

- The Tribunal disagreed with HMRC's blanket approach, ruling that the commercial contract did not equate to direct subsidisation of R&D.

- Collins Construction had autonomy in initiating and specifying the R&D, and the customer did not fund the R&D specifically; rather, it was incidental to the delivery of a wider commercial service.

- The Tribunal emphasised economic and contractual substance over form, aligning with the principles now codified in HMRC’s four-factor test.

- The outcome confirmed that contractors may still be eligible to claim R&D relief, even if the R&D was performed as part of a commercial contract, provided the work was not directly subsidised for R&D purposes.

Implication: This case signalled a shift toward a more nuanced interpretation of R&D eligibility, particularly beneficial for contractors who initiate and bear the risk of innovation.

StageOne Creative Services Ltd v HMRC (2022)

This earlier case also saw theFirst-tier Tribunal rule in favour of the taxpayer, Stage One Creative Services Ltd, which specialises in large-scale creative structures and engineering.

Key Findings:

- The company conducted R&D to solve novel technical challenges, despite the work being embedded in a commercial contract with a client.

- The Tribunal held that R&D relief was not precluded simply because the R&D activities were commissioned within a broader service contract.

- Importantly,Stage One bore the technical uncertainty and financial risk, initiated the methods, and developed proprietary techniques applicable to future projects—hallmarks of genuine R&D ownership.

Implication: The ruling reinforced that contractual context alone does not define eligibility; what matters is the nature of the work, who drives the innovation, and who retains benefit.

Final Thoughts on HMRC’s Updates

These reforms to the UK’s R&D tax relief framework reflect a deeper focus on ensuring that the correct party—namely, the one driving, funding, and benefiting from innovation—receives the incentive. They aim to eliminate uncertainty and reduce the risk of double claims, misclassification, or misuse.

For claimants, this means moving beyond checkbox compliance to a more holistic and strategic approach. Assessing contracts through the lens of HMRC’s four-factor framework—initiation, specification, risk, and benefit—will be crucial. So too will be maintaining clear documentation, aligning commercial agreements with intended tax positions, and adapting to the nuances of international project work.

In short, the new regime demands that companies not just perform R&D, but also demonstrate their leadership and ownership of it. That is the new standard for claiming R&D tax relief in the UK.

Ready to Navigate the New R&D Tax Relief Rules with Confidence?

The updated UK R&D tax relief rules for contracted-out activities introduce a complex framework that demands precision and expertise. As outlined in the article, eligibility now hinges onHMRC’s four-factor test—initiation, specification, financial risk, and benefit—making it critical to align your contracts and documentation with these criteria. Missteps in interpreting these rules or structuring your R&D projects could lead to missed opportunities or HMRC enquiries.

At Copper Tax, we offer a tailored, comprehensive service to maximise your R&D tax relief while ensuring compliance with the new regulations. Our deep understanding of HMRC’s nuanced guidance, including the importance of economic substance over mere technical work, ensures your claim reflects the true ownership and innovation of your project.

Start with a free, no-obligation consultation call to explore your R&D activities, assess eligibility, and estimate the potential tax relief available. Book a call with Claire or Jeremy today to secure the funding you’re entitled to and gain peace of mind in navigating this intricate landscape.

Achieving a robust R&D tax credit claim!

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)